Building a terrible 'IoT' temperature logger

I had approximately the following exchange with a co-worker a few days ago:

Them: “Hey, do you have a spare Raspberry Pi lying around?”

Me: [thinks] “..yes, actually.”

T: “Do you want to build a temperature logger with Prometheus and a DS18B20+?

M: “Uh, okay?”

It later turned out that that co-worker had been enlisted by yet another individual to provide a temperature logger for their project of brewing cider, to monitor the temperature during fermentation. Since I had all the hardware at hand (to wit, a Raspberry Pi 2 that I wasn’t using for anything and temperature sensors provided by the above co-worker), I threw something together. It also turned out that the deadline was quite short (brewing began just two days after this initial exchange), but I made it work in time.

Interfacing the thermometer

As noted above, the core of this temperature logger is a DS18B20 temperature sensor. [Per the manufacturer] (https://www.maximintegrated.com/en/products/sensors/DS18B20.html):

The DS18B20 digital thermometer provides 9-bit to 12-bit Celsius temperature measurements … communicates over a 1-Wire bus that by definition requires only one data line (and ground) for communication with a central microprocessor. … Each DS18B20 has a unique 64-bit serial code, which allows multiple DS18B20s to function on the same 1-Wire bus. Thus, it is simple to use one microprocessor to control many DS18B20s distributed over a large area.

Indeed, this is a very easy device to interface with. But even given the svelte hardware needs (power, data and ground signals), writing some code that speaks 1-Wire is not necessarily something I’m interested in. Fortunately, these sensors are very commonly used with the Raspberry Pi, as illustrated by an Adafruit tutorial published in 2013.

The Linux kernel provided for the Pi in its default Raspbian (Debian-derived)

distribution supports bit-banging 1-Wire over its GPIOs by default, requiring

only a device tree

overlay

to activate it. This is as simple as adding a line to /boot/config.txt to make

the machine’s boot loader instruct the kernel to apply a change to the hardware

configuration at boot time:

|

|

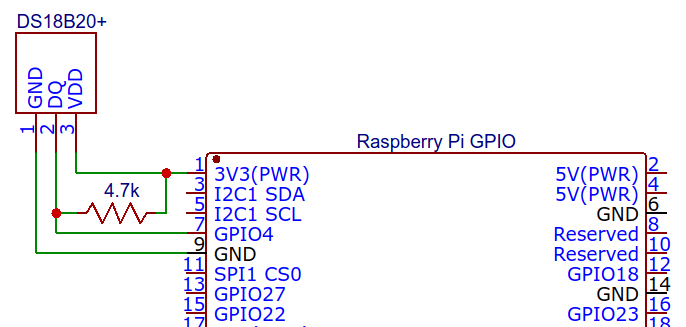

With that configuration, one simply needs to wire the sensor up. The w1-gpio

device tree configuration by default uses GPIO 4 on the Pi as the data line,

then power and grounds need to be connected and a pull-up resistor added to the

data line (since 1-Wire is an open-drain bus).

The w1-therm kernel

module already

understands how to interface with these sensors- meaning I don’t need to write

any code to talk to the temperature sensor: Linux can do it all for me! For

instance, reading the temperature out in an interactive shell to test, after

booting with the 1-Wire overlay enabled:

|

|

The kernel periodically scans the 1-Wire bus for slaves and creates a directory

for each device it detects. In this instance, there is one slave on the bus (my

temperature sensor) and it has serial number 000004b926f1. Reading its

w1_slave file (provided by the w1-therm driver) returns the bytes that were

read on both lines, a summary of transmission integrity derived from the message

checksum on the first line, and t=x on the second line, where x is the

measured temperature in milli-degrees Celsius. Thus, the measured temperature

above was 25.687 degrees.

While it’s fairly easy to locate and read these files in sysfs from a program, I

found a Python library that further simplifies the process:

w1thermsensor provides a simple

API for detecting and reading 1-wire temperature sensors, which I used when

implementing the bridge for capturing temperature readings (detailed more

later).

1-Wire details

I wanted to verify for myself how the 1-wire interfacing worked so here are the details of what I’ve discovered, presented because they may be interesting or helpful to some readers. Most documentation of how to perform a given task with a Raspberry Pi is limited to comments like “just add this line to some file and do the other thing!” with no discussion of the mechanics involved, which I find very unsatisfying.

The line added to /boot/config.txt tells the Rapberry Pi’s boot loader

(a version of Das U-Boot) to pass the

w1-gpio.dtbo device tree overlay description to the kernel. The details of

what’s in that overlay can be found in the kernel source tree at

arch/arm/boot/dts/overlays/w1-gpio-overlay.dts.

This in turn pulls in the w1-gpio kernel module, which is part of the

upstream kernel distribution- it’s very simple, setting or reading the value of

a GPIO port as requested by the Linux 1-wire subsystem.

Confusingly, if we examine the dts file describing the device tree overlay, it

can take a pullup option that controls a rpi,parasitic-power parameter. The

documentation says this “enable(s) the parasitic power (2-wire, power-on-data)

feature”, which is confusing. 1-Wire is inherently capable of supplying

parasitic power to slaves with modest power requirements, with the slaves

charging capacitors off the data line when it’s idle (and being held high, since

it’s an open-collector bus). So, saying an option will enable parasitic power is

confusing at best and probably flat wrong.

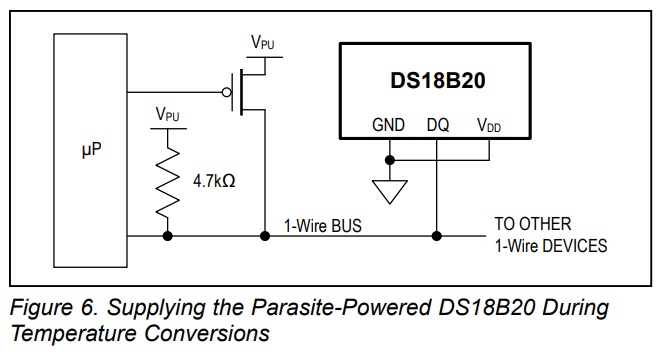

Further muddying the waters, there also exists a w1-gpio-pullup overlay that

includes a second GPIO to drive an external pullup to provide more power, which

I believe allows implementation of the strong pull-up described in Figure 6 of

the DS18B20 datasheet (required because the device’s power draw while reading

the temperature exceeds the capacity of a typical parasitic power setup):

By also connecting the pullup GPIO to the data line (or putting a FET in there

like the datasheet suggests), the w1-gpio driver will set the pullup line to

logic high for a requested time, then return it to Hi-Z where it will idle. But

for my needs (cobbling something together quickly), it’s much easier to not even

bother with parasite power.

In conclusion for this section: I don’t know what the pullup option for the

1-Wire GPIO overlay actually does, because enabling it and removing the external

pull-up resistor from my setup causes the bus to stop working. The documentation

is confusingly imprecise, so I gave up on further investigation since I already

had a configuration that worked.

Prometheus scraping

To capture store time-series data representing the temperature, per the co-worker’s original suggestion I opted to use Prometheus. While it’s designed for monitoring the state of computer systems, it’s plenty capable of storing temperature data as well. Given I’ve used Prometheus before, it seemed like a fine option for this application though on later consideration I think a more robust (and effortful) system could be build with different technology choices (explored later in this post).

The Raspberry Pi with temperature sensor in my application is expected to stay within range of a WiFi network with internet connectivity, but this network does not permit any incoming connections, nor does it permit connections between wireless clients. Given I wanted to make the temperature data available to anybody interested in the progress of brewing, there needs to be some bridge to the outside world- thus Prometheus should run on a different machine from the Pi.

The easy solution I chose was to bring up a minimum-size virtual machine on Google Cloud running Debian, then install Prometheus and InfluxDB from the Debian repositories:

|

|

Temperature exporter

Having connected the thermometer to the Pi and set up Prometheus, we now need to glue them together such that Prometheus can read the temperature. The usual way is for Prometheus to make HTTP requests to its known data sources, where the response is formatted such that Prometheus can make sense of the metrics. There is some support for having metrics sources push their values to Prometheus through a bridge (that basically just remembers the values it’s given until they’re scraped), but that seems inelegant given it would require running another program (the bridge) and goes against the how Prometheus is designed to work.

I’ve published the source for the metrics exporter I ended up writing, and will give it a quick description in the remnants of this section.

The easiest solution to providing a service over HTTP is using the

http.server module, so

that’s what I chose to use. When the program starts up it scans for temperature

sensors and stores them. This has a downside of never returning data if a sensor

is accidentally disconnected at startup, but detection is fairly slow and only

doing it at startup makes it clearer if sensors are accidentally disconnected

during operation, since reading them will fail at that point.

|

|

The request handler has a method that builds the whole response at once, which is just plain text based on a simple template.

|

|

do_GET is called by BaseHTTPRequestHandler for all HTTP GET requests to the

server. Since this server doesn’t really care what you want (it only exports one

thing- metrics), it completely ignores the request and sends back metrics.

|

|

The http.server API is somewhat cumbersome in that it doesn’t try to handle

setting Content-Length on responses to allow clients to keep connections open

between requests, but at least in this case it’s very easy to set the

Content-Length on the response and correctly implement HTTP 1.1. The

Content-Type used here is the one specified by the Prometheus documentation for

exposition

formats.

The rest of the program is just glue, for the most part. The

console_entry_point function is the entry point for the

w1therm_prometheus_exporter script specified in setup.py. The network address

and port to listen on are taken from the command line, then an HTTP server is

started and allowed to run forever.

As a server

As a Python program with a few non-standard dependencies, installation of this

server is not particularly easy. While I could sudo pip install everything and

call it sufficient, that’s liable to break unexpectedly if other parts of the

system are automatically updated- in particular the Python interpreter itself

(though Debian as a matter of policy doesn’t update Python to a different

release except as a major update, so it shouldn’t happen without warning). What

I’d really like is the ability to build a single standalone program that

contains everything in a convenient single-file package, and that’s exactly what

PyInstaller can do.

A little bit of wrestling with pyinstaller configuration later (included as the

.spec file in the repository), I had successfully built a pretty heavy (5MB)

executable containing everything the server needs to run. I placed a copy in

/usr/local/bin, for easy accessibility in running it.

I then wrote a simple systemd unit for the temperature server to make it start

automatically, installed as

/etc/systemd/system/w1therm-prometheus-exporter.service:

|

|

Enable the service, and it will start automatically when the system boots:

|

|

This unit includes rather more protection than is probably very useful, given the machine is single-purpose, but it seems like good practice to isolate the server from the rest of the system as much as possible.

DynamicUserwill make it run as a system user with ID semi-randomly assigned each time it starts so it doesn’t look like anything else on the system for purposes of resource (file) ownership.ProtectSystemmakes it impossible to write to most of the filesystem, protecting against accidental or malicious changes to system files.ProtectHomemakes it impossible to read any user’s home directory, preventing information leak from other users.PrivateTmpgive the server its own private/tmpdirectory, so it can’t interfere with temporary files created by other things, nor can its be interfered with- preventing possible races which could be exploited.

Pi connectivity

Having built the HTTP server, I needed a way to get data from it to Prometheus. As discussed earlier, the Raspberry Pi with the sensor is on a WiFi network that doesn’t permit any incoming connections, so how can Prometheus scrape metrics if it can’t connect to the Pi?

One option is to push metrics to Prometheus, using the push gateway. However, I don’t like that option because the push gateway is intended mostly for jobs that run unpredictably, in particular where they can exit without warning. This isn’t true of my sensor server. PushProx provides a rather better solution, wherein clients connect to a proxy which forwards fetches from Prometheus to the relevant client, though I think my ultimate solution is just as effective and simpler.

What I ended up doing is using autossh to open an SSH tunnel at the Prometheus server which connects to the Raspberry Pi’s metrics server. Autossh is responsible for keeping the connection alive, managed by systemd. Code is going to be much more instructive here than a long-form description, so here’s the unit file:

|

|

Installed as /etc/systemd/system/autossh-tunnel@.service, this unit file tells

systemd that we want to start autossh when the network is online and try to

ensure it always stays online. I’ve increased RestartSec from the default 100

milliseconds because I found that even with the dependency on

network-online.target, ssh could fail when the system was booting up with DNS

lookup failures, then systemd would give up. Increasing the restart time means

it takes much longer for systemd to give up, and in the meantime the network

actually comes up.

The autossh process itself runs as a system user I created just to run the

tunnels (useradd --system -m autossh), and opens a reverse tunnel from port

9000 on the remote host to the same port on the Pi. Authentication is with an

SSH key I created on the Pi and added to the Prometheus machine in Google Cloud,

so it can log in to the server without any human intervention. Teaching systemd

that this should run automatically is a simple enable command away1:

|

|

Then it’s just a matter of configuring Prometheus to scrape the sensor exporter. The entire Prometheus config looks like this:

|

|

That’s pretty self-explanatory; Prometheus will fetch metrics from port 9000 on the same machine (which is actually an SSH tunnel to the Raspberry Pi), and do so every 15 seconds. When the Pi gets the request for metrics, it reads the temperature sensors and returns their values.

Data retention

I included InfluxDB in the setup to get arbitrary retention of temperature data- Prometheus is designed primarily for real-time monitoring of computer systems, to alert human operators when things appear to be going wrong. Consequently, in the default configuration Prometheus only retains captured data for a few weeks, and doesn’t provide a convenient way to export data for archival or analysis. While the default retention is probably sufficient for this project’s needs, I wanted better control over how long that data was kept and the ability to save it as long as I liked. So while Prometheus doesn’t offer that control itself, it does support reading and writing data to and from various other databases, including InfluxDB (which I chose only because a package for it is available in Debian without any additional work).

Unfortunately, the version of Prometheus available in Debian right now is fairly old- 1.5.2, where the latest release is 2.2. More problematic, while Prometheus now supports a generic remote read/write API, this was added in version 2.0 and is not yet available in the Debian package. Combined with the lack of documentation (as far as I could find) for the old remote write feature, I was a little bit stuck.

Things ended up working out nicely though- I happened to see flags relating to InluxDB in the Prometheus web UI, which mostly have no default values:

storage.remote.influxdb-urlstorage.remote.influxdb.database = prometheusstorage.remote.influxdb.retention-policystorage.remote.influxdb.username

These can be specified to Prometheus by editing /etc/defaults/prometheus,

which is part of the Debian package for providing the command line arguments to

the server without requiring users to directly edit the file that tells the

system how to run Prometheus. I ended up with these options there:

|

|

The first option just makes Prometheus keep its data longer than the default,

whereas the others tell it how to write data to InfluxDB. I determined where

InfluxDB listens for connections by looking at its configuration file

/etc/influxdb/influxdb.conf and making a few guesses: a comment in the http

section there noted that “these (HTTP endpoints) are the primary mechanism for

getting data into and out of InfluxDB” and included the settings

bind-address=":8086" and auth-enabled=false, so I guessed (correctly) that

telling Prometheus to find InfluxDB at http://localhost:8086/ should be

sufficient.

Or, it was almost enough: setting the influxdb-url and restarting Prometheus,

it was logging warnings periodically about getting errors back from InfluxDB.

Given the influxdb.database settings defaults to prometheus, I (correctly)

assumed I needed to create a database. A little browsing of the Influx

documentation and a few guesses later, I had done that:

|

|

Examining the Prometheus logs again, now it was failing and complaining that the

specified retention policy didn’t exist. Noting that the Influx documentation

for the CREATE DATABASE command mentioned that the autogen retention policy

will be used if no other is specified, setting the retention-policy flag to

autogen and restarting Prometheus made data start appearing, which I verified

by waiting a little while and making a query (guessing a little bit about how I

would query a particular metric):

|

|

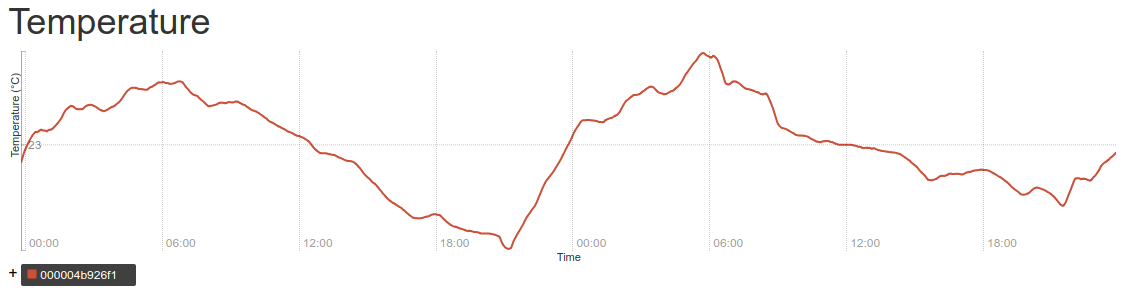

Results

A sample graph of the temperature over two days:

The fermentation temperature is quite stable, with daily variation of less than one degree in either direction from the baseline.

Refinements

I later improved the temperature server to handle SIGHUP as a trigger to scan

for sensors again, which is a slight improvement over restarting it, but not

very important because the server is already so simple (and fast to restart).

On reflection, using Prometheus and scraping temperatures is a very strange way to go about solving the problem of logging the temperature (though it has the advantage of using only tools I was already familiar with so it was easy to do quickly). Pushing temperature measurements from the Pi via MQTT would be a much more sensible solution, since that’s a protocol designed specifically for small sensors to report their states. Indeed, there is no shortage of published projects that do exactly that more efficiently than my Raspberry Pi, most of them using ESP8266 microcontrollers which are much lower-power and can still connect to Wi-Fi networks.

Rambling about IoT security

Getting sensor readings through an MQTT broker and storing them to be able to graph them is not quite as trivial as scraping them with Prometheus, but I suspect there does exist a software package that does most of the work already. If not, I expect a quick and dirty one could be implemented with relative ease.

On the other hand, running a device like that which is internet-connected but is unlikely to ever receive anything remotely looking like a security update seems ill-advised if it’s meant to run for anything but a short amount of time. In that case having the sensor be part of a Zigbee network instead, which does not permit direct internet connectivity and thus avoids the fraught terrain of needing to protect both the device itself from attack and the data transmitted by the device from unauthorized use (eavesdropping) by taking ownership of that problem away from the sensor.

It remains possible to forward messages out to an MQTT broker on the greater internet using some kind of bridge (indeed, this is the system used by many consumer “smart device” platforms, like Philips' Hue though I don’t think they use MQTT), where individual devices connect only to the Zigbee network, and a more capable bridge is responsible for internet connectivity. The problem of keeping the bridge secure remains, but is appreciably simpler than needing to maintain the security of each individual device in what may be a heterogeneous network.

It’s even possible to get inexpensive off-the-shelf temperature and humidity sensors that connect to Zigbee networks like some sold by Xiaomi, offering much better finish than a prototype-quality one I might be able to build myself, very good battery life, and still capable of operating in a heterogenous Zigbee network with arbitrary other devices (though you wouldn’t know it from the manufacturer’s documentation, since they want consumers to commit to their “platform” exclusively)!

So while my solution is okay in that it works fine with hardware I already had on hand, a much more robust solution is readily available with off-the-shelf hardware and only a little bit of software to glue it together. If I needed to do this again and wanted a solution that doesn’t require my expertise to maintain it, I’d reach for those instead.

-

Hostname changed to an obviously fake one for anonymization purposes. ↩︎